BtF 6: God’s Dice

(This is the sixth post in a series about our precarious existence “Between the Falls”. If you haven’t read any of the previous ones, you might want to go all the way back and begin with the first, which explains the idea behind this series, but here it is in a nutshell: technological progress and the move towards transhumanism have us on the precipice of a second great fall of man, the first one being that famous, symbolic or literal, bite of apple that drove us out of our primal state of ignorance and grace. This post draws on a podcast episode I did in 2020 called Through the Simulation Hypothesis, Darkly. I don’t want to give too much away, but there will be talk of billiards, multi-armed bandits, Waze, asteroids, punch cards, and tumblers filled with ping pong balls.)

What are we doing here, anyway?

That’s a big question, and maybe one that can’t be answered. But I think I can make progress on, or at least speculate about, a related but narrower question. Many people, myself included, believe we exist inside something like a computer simulation. If that’s the case, what might be the purpose of that simulation?

Before directly attempting to answer that question, I want to note that the simulation hypothesis is the latest in a pattern of reframing how we view the nature of our universe, and ourselves, along with our technological advances. With the invention of the clock came the model of the clockwork universe, and the idea that human beings were deterministic machines, predestined to act exactly as they do, just as the gears of a clock completely determine where each hand will be and when. With the rise of the computer, the universe itself became a calculating machine, computing at plank-length intervals where everything should be and what it would be doing.

Early pioneers in the field of computing argued that the human brain was our CPU, taking in input and directing our actions based on internal algorithms. Now that humans are capable of creating sophisticated virtual worlds, it only makes sense that we should re-imagine our world itself as a simulation, and ourselves as characters, or avatars, within that virtual world.

So, are we just projecting one more tech advancement on the universe and ourselves, or is there something more at play?

If there is, I think that something else is related to how our most recent advances in computing are not just more sophisticated and powerful, but also alter the dynamic between computers and humans in a subtle but profound way.

From the very first abacus, our tools have helped us calculate. But now we, as humans, often do the calculating on behalf of computers. I discussed this previously in the second Between the Falls post, but briefly, if you’ve ever used Waze to direct you from downtown to the airport, you become a calculator for how long it takes to drive from downtown to the airport. You, along with everyone else using the app to go in that general direction. Waze will suggest the best route, but that route, along with the estimation of how long it will take, has been calculated by all all the other drivers, and as we drive we’re calculating it for future drivers.

This if different in a subtle, but very important way from saying that we provide the data input used by computers. That’s been true forever, or at least since researchers put data on punch cards to be fed into huge mainframes. This goes well beyond that. To function, Waze needs not us not just to feed it a set of static data, but to be synergistic participants. As non-deterministic calculation agents, humans are an indispensable part of the Waze algorithm. For Waze to work, we have to do the work.

This shift, in my view, suggests a theory of what our universe, if it’s a simulation, might be designed to do.

When math isn’t enough

Humans create virtual worlds to play in, but we also run simulations because sometimes, math isn’t enough. That is, just as we can’t figure out driving times a priori, there are lots of other problems where we can’t just write down an equation and solve for x. For even a simple, closed system, like computing the paths of idealized billiard balls after a break, there’s no golden formula to decide where the 8-ball will be after three seconds. To know that, you have to either virtually simulate the break, with as much precision as you possibly can, or you have to grab a real pool cue and break a real set of balls. Every such break is you computing something.

If we live in a simulation, then maybe we exist for the same reason, broadly speaking, that we create simulations: it may be the only way to figure certain things out, or to test out scenarios.

If this is the case, then lots really big questions follow immediately. Among them, What are we computing? and Does this tell us anything about free will?

If our sub-universe exists as a way to test out scenarios, or to help solve a problem that our creators one level up are having, what exactly are we solving for? To answer that, all we can do is extrapolate based on our own most challenging problems, and then do some speculating based on our own experience.

For us as humans, what kinds of problems seem to require the highest levels of computing power? Generally, these problems involve making predictions in complex systems where noise rules, and small changes to initial conditions can lead to very different outcomes. Think about the billiard ball example, or a weather model designed to tell us if it will rain in our city in two weeks. Or go a step further, and think about how hard it is for us to predict the effect on our climate of various human interventions. These problems tend to be as much about probable scenarios as they are about coming up with a single right answer.

Assuming that we don’t serve as entertainment for the level above, my guess is we are a tool for solving a problem that’s intractable using the kind of tools we ourselves already have, because, logically, the tools in our parent universe must be at least as powerful as the tools we have within our simulated sub-universe.

In short, it would make sense that we ourselves — along with everything else in our universe — exist as a much more advanced version of the machine learning or AI algorithms that we use to make predictions about the probability of events under different scenarios in a highly complex, noisy environment.

In even shorter, we are a key part of their AI system.

Suppose that’s true. Is there any way we can know more specifically what problems we are, collectively, woking on?

The ghosts in the machine

Years ago, I created an evolutionary algorithm in the programming language R. The goal was to predict the price movements of asset classes, including stocks and commodities. It worked by having virtual prediction agents compete with each other. With each tick of the clock, the worst agents were killed off (or tested with their predictions flipped), while the best ones survived, mutated, and had “children.” (As an aside, this is related to something called the multi-armed bandit problem, which I find fascinating, and maybe you would to.)

The agents inside my evolutionary algorithm, I am confident, lacked consciousness, certainly in any way that might be comparable to human consciousness. But we have it, which is strange, and suggests the question, If we are living in a simulation, what role could consciousness possibly play in that?

One possible answer is that, just as our most powerful prediction algorithms use some element of randomness, consciousness is key to that randomness.

This is a tricky argument and it embeds some assumptions, but I’ll try and unpack and explain. We are now assuming that:

We live in some kind of simulated universe.

Our universe exists as a prediction model or problem solving algorithm for the universe above us.

Our role is to help explore the solution space for that problem.

Within that context, I’m now asserting that the role of consciousness is to inject randomness into the system, even beyond what’s baked into our universe at the quantum level, or perhaps as a more sophisticated expression of it.

How does that work? Because we are self-conscious, we can reason about the future and pick from among possible actions and desired outcomes. So even if the universe was deterministic and we could calculate the future, consciousness gives us the ability to choose other futures, destroying this very determinism. We are the ghosts in the machine, which is exactly the conclusion I came to when trying to figure out if the use of generative AI was summoning demons.

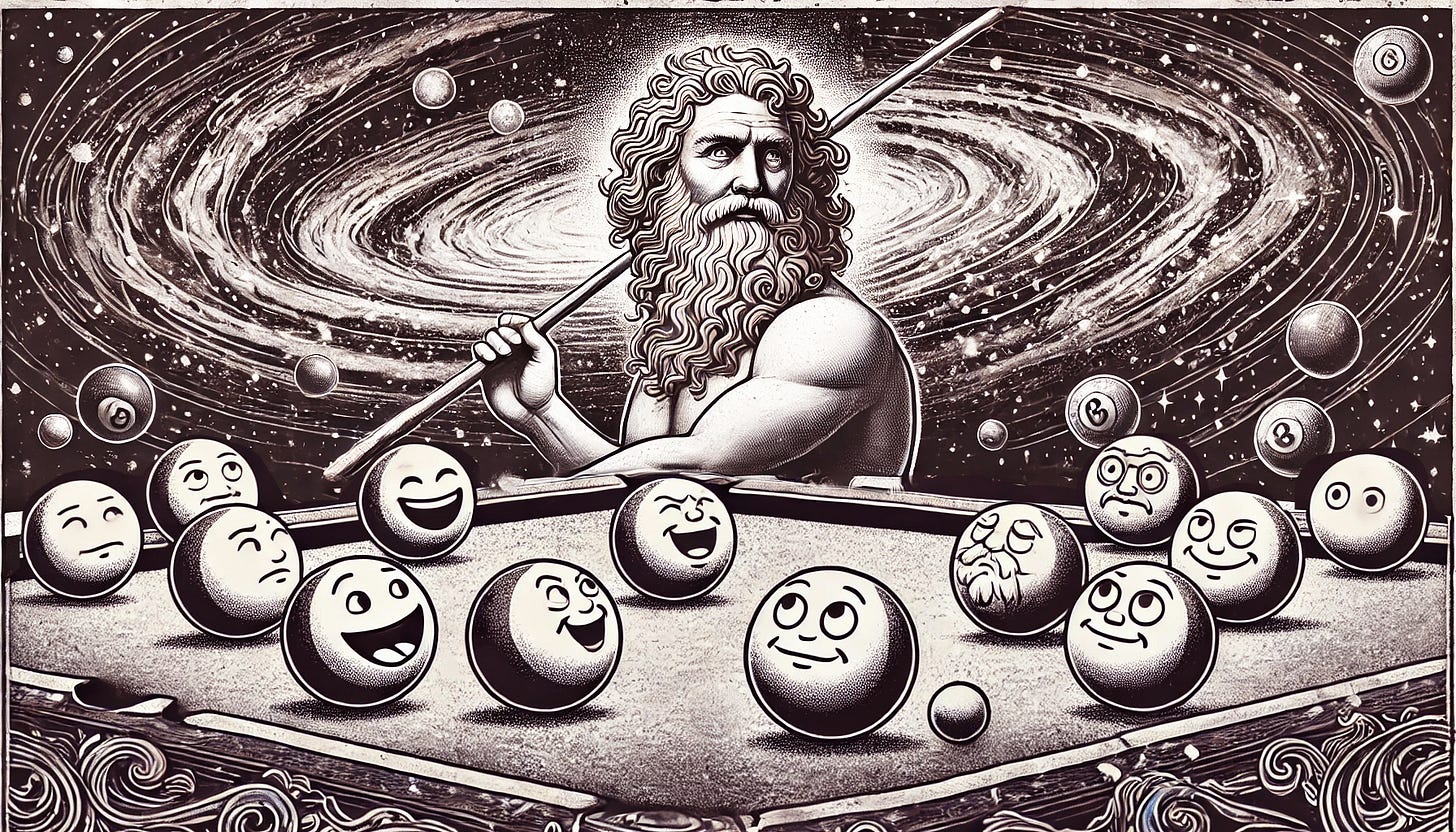

I understand that this argument might seem bizarre at first, especially in its implications. In particular, this turns consciousness, and possibly even free will, into a side effect of our role in this universe. In this scenario, we are, in effect, complex, self-rolling dice.

There’s another reason we might be self-conscious. You may have noted I still haven’t speculated on exactly what problem we are here in this sub-universe to solve. Take a deep breath, as we’re about to tumble down a rabbit hole here.

Existence for the sake of the existent

Suppose we really are, as the bible suggests, created in our Creator’s image, which is just clunky way of saying we resemble Him. Or Them, as the plural pronoun is often used for God, perhaps in a kind of “royal we” way, but let’s treat it as a literal we. As in, our God is our creators, with an “s”. If so, then of course we would be conscious, we are replicants of Them, and They are conscious. In other words, maybe the universes are humans all the way down (or up).

Still, though, why generate a sub-universe of conscious agents that resemble you? What problem could be so big that beings one level up are incapable of solving it directly, that is without simulating an entire other universe of creatures that are in some ways like them?

Now we get to the really speculative part. Suppose in the not-too distant future we here in this universe gain the ability to create fully immersive synthetic worlds populated by sophisticated, self-conscious agents. What problem would we want those agents to help solve for us? To me, the answer to that question is obvious. If you handed the keys to that simulation machine over to me, the first problem I’d want to work on is how do we prevent humans from self-destructing. What combination of technology, ideas, culture, and policy can solve for the problem of navigating the transition to trans-humanism without ending in disaster, or allow us to opt out of the second great fall entirely? As noted from the beginning of this series, the second great fall of man gives us the powers of gods. Maybe our simulated universe exists because the creatures in the level above, now endowed the power of gods, are trying to figure out how not to self-destruct with these newfound powers. Or to collectively opt out of the power itself?

If your head hurts, it might be because this theory, if true, is obviously true, which is a tautology but also not, in the way that saying “it is what it is” somehow conveys information even though at a formal level it says nothing. It’s because once you assume it’s true, everything about our human world makes a lot more sense. For example, why do we have so many religious myths that all reinforce the same idea of not trying to imitate the creator? Like don’t fly too close to the sun, don’t build towers to the heavens, no stealing fire from the gods, and whatever you do, don’t seek immortality. What’s the point of all those enduring stories?

Maybe the way I’ve setup the question makes the answer obvious. If not, note that all these myths are warnings that, if heeded, would have the effect of slowing, or blocking, the path to transhumanism, and its accompanying power to destroy humanity, or create a dystopia for the inhabitants of that universe. I’m reminded of one of the proposed solutions for how to create a warning marker for buried nuclear waste that would still be intelligible thousands of years later. The most promising solution might be to embed the warning into religion or culture with an allegorical story. That’s because while almost everything humans built thousand of years ago has crumbled and been covered up by dirt, we’re still discussing the biblical origin story for human beings and a bunch of other ancient myths. Buildings turn to ruins. Languages evolve and are lost. Mythology endures.

A dangerous role

Backing out of the rabbit hole for a moment, what exactly am I suggesting here? My theory is that we are God’s dice, or God’s computers in the Wazian sense. Also, as when I was building my prediction model in R, I didn’t just run the code a single time with a single agent, but ran it thousands of times with multiple agents each time, and tweaked the code after each run. The entire system followed an evolutionary path. If we are what I think we are, we are almost certainly one of many, many evolved and forked simulations that have been run and will be run. This, by the way, would explain how both our universe and DNA-based evolution seems to be so well tuned at the meta level, a topic I discussed previously.

If true, what does this theory mean for us, in our particular instance of the simulation, as we near the second great fall of man? The bad news is that we only exist because our creators are worried that we might self-destruct at just this moment. Also, there are probably an untold number of simulations that have already ended in a failure state. After all, if this was a solved problem, why would still be here, consuming resources in the universe above, just like our AI’s consume electricity like mad? But then, if it isn’t a solved problem, what are the chances we’ll be the first ones to figure it out?

The good news is that, if this theory is correct, we have evidence that we’re not in the first simulation to be working on the problem in the form of those well tuned tuning parameters, and that also makes sense from a statistical point of view. Based on what’s known as the “Principle of Indifference,” if you sample at random from a process that extends over some dimension for an unknown length, your best point estimate for that sample would be that you sampled the midpoint. That’s a bit complicated, so let’s look at a simpler problem. Suppose I told you to close your eyes and pull a single numbered ping pong ball out of a hopper, like they do for the lottery. If you have no idea how many balls are in the hopper, but you had to guess based on that single sample, it might be reasonable to guess that the total number is twice as big as the number you picked. After all, if the hopper was thoroughly tumbled, you are equally likely to pick a number above or below the half-way point.

As applied to us as humans trying to figure out how much longer we have until the end comes, this line of reasoning is sometimes called the “Doomsday Argument,” for what should be obvious reasons. It suggests that our best guess is that we exist in the midpoint of time between creation and elimination, which is comforting, I guess, but I suspect that if we do live in a simulation created for the purpose I’m suggesting, the process of generating, forking, and rebooting these simulations is way more complicated than we could possibly imagine. If so, then us noticing we live in a simulation is nothing at all like picking a random moment in time from a tumbler of numbered moments.

So in the end, assuming my line of reasoning is correct, we still might have no way of knowing our chances of making it through the asteroid field, or navigating away from it entirely, at this point.