BtF 2: Summoning Demons

(Last week was the first in a series of posts about our precarious existence Between the Falls. If you haven’t read that first one, you might want to go back and do so now, but here is the idea behind this series, in a nutshell: A number of technologies, and the move towards transhumanism, have us on precipice of a second great fall, the first one being that famous, symbolic or literal, bite of apple that drove us out of our primal state of ignorance and grace. I don’t want to give too much away about this weeks post, but there will be talk of lorem ibsum, nihilists, Fiverr, Forest Gump, and atomic shadows. Stick to the end as I have a brief postscript based on an experience I just had, and a comment from the main person mentioned in this post.)

Are we summoning demons with AI?

That’s the question I’ll try and answer in this post. I’m asking because it’s the belief of my very first podcast guest, back in 2020, Vin Armani, more recently know as the Cyprian. As a devout member of the Orthodox Christian Church, he means demons in a literal sense. For my part I’m not convinced of the existence of actual demons, but I have no doubt that some things are genuine moral and spiritual transgressions. Evil exists, whether or not it’s connected to demonic spirits or possession, so that’s what I’ll be looking for evidence of in our use of AI tools. I’ll be taking his idea seriously, if not literally.

In terms of his specific claim, the Cyprian is talking about the use of generative AI tools, ones like ChatGPT and Stable Diffusion. These produce text and images based on the prompts you give them. To be ever so slightly technical, ChatGPT falls into the category of Large Language Models, or LLMs. These take in huge amounts of text, turn that text into data, and then use that data to decide which words are most likely to follow others when generating a response to your queries. If you have a deep knowledge of LLMs and are cringing at my hand-wavy explanation, my apologies, just say in your head all the caveats and complexities I’ve omitted and you’ll be fine. The image generators work a little differently, and sometimes seem even more magical, but for the sake of discussing whether we are summoning demons, I don’t think that matters much, so I’m going to focus on the text stuff.

Before evaluating the claim about demons, I need to talk about the idea of marginality. I’m a very strong believer in marginality, and also in the idea that you can always find a single hair that prevents someone from being bald, so I’m going to start by explaining those two things, which will seem to be in conflict with each other but really aren’t, and at some point it should be clear why I’ve started this sermon at such an odd place. The idea of marginality, for me, is that every little thing has an effect. Or, put another way, there is nothing so small that it doesn’t have an effect. A different way to put this is that everything counts, in all amounts. Yet one more way to put this is that all seemingly magic thresholds, or precise moments, when A turns to B, these are suspect, which is why I’m drawn to the idea of panpsychism, the theory that holds that some form of very rudimentary consciousness is embedded in all matter, and there is no single magic moment when biological life goes from unconscious to conscious. Instead, there are only increasingly complex webs of harmonics. For what it’s worth I’m no longer so drawn to the idea of panpsychism, but only because I’ve changed how I view the universe.

For those of you I may have lost, here’s the summary. Marginality is about never rounding down the effect of something to zero, and that there are no thresholds with alchemical powers. In other words, no matter how much lead you melt into a pot, it’s never going to magically turn into gold, but every single atom of lead you add to the pot will make it heavier.

The idea of the hair that keeps you from being bald is that, well, I’m not bald. Not yet anyway. I’m blessed by genetics, and perhaps helped by my decision to stop shampooing on a regular basis decades ago. I think everyone will agree with my self assessment as not-bald. On the other hand, I think we could all agree that actor Telly Savalas, at least by the time he played Kojak, was bald.

So if being bald is a binary, in that you either are bald or you aren’t, that means that if you began plucking the hairs off my head, and please don’t do that, but if you did, at some point I would go from not bald, to bald. The transition point, necessarily, has to involve the removal of a single hair. You can’t just keep plucking hairs one by one forever, so there has to be a single, threshold hair, that makes all the difference, and it’s generally not the very last one. A man with one hair is still bald.

If you’re still following, then you’ve probably arrived at the point where it seems like we have two conflicting ideas. The idea of marginality without a magic threshold, and the idea that there’s also some hair, some one individual hair, that makes all the difference in what we consider something.

The way to reconcile these ideas is return to an analogy I already gave. Suppose you have a pot you are filling with lead, one atom at a time. That will never magically turn into gold. It just gets some marginal amount heavier with each atom. If the pot was hanging from a thin chain above a fireplace, there’d be some amount of lead that, when added, would cause the chain to break and the pot to tumble into the fire. Maybe we are certain that the chain can support one kilogram of weight, but not 1000 kilograms. Then we also know that by adding lead to it, one atom at a time, there has to be a single atom that makes the difference, and topples the pot.

Years ago, I built a simple fake text generator in Python, because for some reason I needed placeholder text with real English words that formed real looking sentences, and not the standard filler text that you might know by its first two words, Lorum Ibsum. I’m not worried that, in running those twenty lines of code to generate vaguely real seeming sentences, I was summoning demons. And, if I understand the Cyprian’s position, in this case I don’t think he wouldn’t be so worried about it either. But if my generator is entirely fine, as in certified demon free, but to use ChatGPT is to summoning demons, what’s going on here? If you started with my program, and then began tweaking the code one line at a time, is there some moment at which magic occurs, and demons are introduced into the system?

As far as I can tell, the Cyprian isn’t declaring that there is some magic threshold at when the summoning begins. Nor is he making the panpsychist-style argument that even more basic generative processes, like rolling dice, are, in some infinitesimal way, summoning demons. I think what the Cyprian is doing is demanding that everyone pick their line, no matter how arbitrary, because if you have no line, you have no way to keep out the demons. But, if there’s no magic moment when the demons get it, why do we need a threshold? How, and when, did the demons slip in, on the coding path from my dumb text generator to the eerily human-like output ChatGPT?

Setting aside, for the moment, our hunt for a back door that will let the ghost into the machine, I’m generally sympathetic to the idea that we need to pick lines, especially when it comes to moral matters. In general, if you have no hard lines, you have no moral boundaries, and you have no morality. Full stop. If for you no hill is a hill to die on, then you’re either a coward or a nihilist. Or both.

Let’s talk about napkins for a moment, and yes, I do like to jump around in topics. I do promise to eventually connect the dots, though. Have you ever taken more napkins from a restaurant than were absolutely needed for the meal that you had there? I have, and generally feel no remorse about doing so, even though I think there is a point at which one’s entitlement to a reasonable number of napkins as part of their meal becomes mooching and then becomes outright stealing. But I couldn’t give you exact limits for those transitions, nor would I say I have a hard line for how many napkins is too many.

Maybe it would be more accurate to say what I have is a fuzzy threshold, but even this is contextual, and most of the time the answer to the question “how many napkins is unacceptable” would be the always unsatisfying, “I can’t tell you, but I know it when I see it.” Sure, I might be able to set some bounds, as in, it’s always acceptable to take a single extra napkin, even if you are going to put it in your car to dispose of gum you might chew at some later date. At the other end, barring some clear emergency, I think it’s for sure wrong to open up the napkin dispenser and pull out a six inch stack of napkins. But this is fine to do in an emergency, and I have in fact my wife did just that, once years ago when she saw a guy split his head open on a curb just outside the fast food restaurant she was in. Am I ashamed of her decision to grab “all the napkins”? Not at all. I think it was the right thing to do, and I don’t think she’s morally obliged to compensate Wendy’s for forcibly donating their napkins to the cause of nursing that guy’s head wound.

In the end, napkins are just napkins, so let me pick a much more controversial topic to make the moral calculus clear. Do I think that abortion is ever right, as in good? No. No I don’t. Do I think abortion is sometimes better than the alternative? Unquestionably yes, and you almost certainly do too, unless you think terminating a 1 week old ectopic pregnancy is worse that letting it grow until both the mom and baby die with (almost 100%) certainty. We can have endless arguments about how bad abortion is under one circumstance or another, and I think there has to be a separate conversation about the wisdom of laws outlawing abortion, but as a marginalist, the only hill I’d die on is that, all other things being equal, abortion at 9 months is unquestionably worse than abortion at 9 days and that, from a moral perspective, there’s also no magic moment when it goes from good to bad. Each day is a little worse than the last to perform a D&E.

If it seem like I’m doing a lot of talking around the issue of whether using ChatGPT is immoral, a sinful conjuring up of demons, you’re not wrong. I don’t think the question can be answered directly, as in, Show me the line of code that’s demonic? That’s like peering into that guy’s cracked open skull outside of Wendy’s and trying to find which dendrite is the one that’s responsible for his consciousness. It makes no sense. We don’t know how human consciousness works, but we do believe it exists, even if we can’t figure out exactly how all those dendrites, along with all that other stuff, make it possible.

Maybe with models like ChatGPT, we’ve reached a level of complexity that’s similar to the human brain, at least in terms of our ability to understand what’s going it. Could I describe what those millions of lines of code are really doing, beyond in a hand-wavy way, like what I presented at the beginning of this talk? I might be able to get closer, just as we can do better in explain the brain than just saying it’s a bunch of dendrites and axons and synapses split into two linked hemispheres. But the actual model used by a modern, generative AI model isn’t really all that compressible or interpretable, you can only run it, see what results it gives, then make changes to the code and see what that does.

If you wanted an exact, functional clone of ChatGPT, you’d need way more than just time to study the math behind concepts like transformers and encoders and attention and embeddings. You’d need to examine the millions of lines of code, and you’d need access to the same collection of terabytes of training data ChatGPT used, because the model and the data are tightly coupled. If you want your generative AI to correctly answer a question about where the Iberian peninsula is, it will have to be fed enough source material linking Spain and the Iberian peninsula. How do you know how much material is enough? Trial and error. And the same goes for every other query, as well as the chat bot’s personality. All that has to be run to be tested, and it will depend on the training data and all the other code. Basically, models like ChatGPT are black boxes.

What this means is that, if there are demons hiding in the code, we likely would never find them, just as how we can endless pick apart the human brain with chemistry or biology or physics without ever discovering where our ghost, our distinctly human form of consciousness, lives, or how it arrises. And yet I have it, and I assume that you do too.

So what are the moral implications of building a system that can’t be explained, or modeled, or reasoned about, any more than we can reason about how certain atom configurations somehow produce our human ability to experience things? We are now very much in technological terra incognito, and incapable of predicting what might emerge from a ten terabyte stew of ever updating data and millions of lines of code with feedback loops. If we built a demon, how would we know?

The Forrest Gump answer might be to say demons are as demons do, which is a bit like the biblical idea that you know a tree by its fruits. But what exactly are the fruits of AI?

One of those fruits is the impact that the use of generative AI will have have on humans, and on our society. As AI takes over more and more of our artistic creation and decision making, it would appear that we are outsourcing our humanity to machines. This is, to me, the heart of what it means to be on the brink of a second fall of man. When Vin Armani the Cyprian says that AI isn’t an extension of our tools, but rather an “alien consciousness”, I understand that to mean alien as in “other”, foreign, exogenous. And I agree, even if I’m not convinced that generative AI is conscious in any way we would recognize as human or even animal. But then again, that might be true of the consciousness of an actual alien, as in a little green man. Who knows if they would seem conscious in a way that’s recognizable to us?

The point is, generative AI isn’t a hammer. It’s not a substitute for, or mere enhancer of, our physical strengths. It does things we think of as uniquely human. It can have a conversation. Give advice. Summarize a book. Make compelling art. Teach science. Write a love letter for us. And if that last one seems especially creepy, it seems worth asking why.

Human beings are constantly doing things that are utilitarian. But also we do spiritual things. Like all definitional bifurcations, this one gets fuzzy in the middle, but it’s a distinction we hold to strongly nonetheless, especially in non-animist cultures. For us, there are things we do that we consider purely utilitarian, unthinking, uncreative. The invention of a motorized tractor to plow the farmer’s fields has huge economic implications, but doesn’t pose a spiritual crisis for us. The tractor’s motor replaces a team of oxen, as in literal beasts of burden, not human beings doing uniquely human things. Generative AI, and expert systems, these cut much closer to the heart of what we think of as human’s unique skills as thinkers and creators. If you believe we have a soul, as distinct from those beastly oxen, it’s because we can paint the Mona Lisa and land on the moon and write sappy but earnest love letters. We passed though a portal with that first great fall of man, and in exchange for the burden of sin, we gained the ability to self reflect, which gave us all these other powers.

If calling generative AI tools demonic is to posit a ghost in those machines, how could that ghost have gotten there?

Before going into a couple answers to that question, let me be clear about my own opinion as to whether there is a ghost in ChatGPT. Having now spent dozens of hours playing with that service and other LLM’s, I’m not seeing any evidence of actual intelligence. What I find is the opposite. While these tools are amazingly good at synthesizing and summarizing existing knowledge, they can’t reason or self reflect in the slightest. I once spent over an hour trying to get an AI to come up with an efficient way to tile a rectangular floor with rectangular tiles. It couldn’t even generate a working solution, let alone the most efficient way. I could get it to generate apologies for failing, but could never steer it closer to a solution. I have heard from others that pervious versions of these conversations bots, before they were burdened with concerns about abetting criminals or deviants or being offensive in one way or another, were actually smarter. In other words, wokeness really is a mind virus that induces brain damage. But as a newer user of ChatGPT, I can’t confirm this with my own experience. Nor do I see how marginal improvements to a sophisticated next-word predictor get you to a ghost in the machine, even with the million lines of code and terrabytes of data.

But how about if you added in some way of doing sanity checking in real time? I suspect some models already have this, but it’s tuned to look for those kind of policy violations I mentioned. I’ve seen this happen many times when trying to generate images, where I ask for something and then, after taking long enough to generate an image, the model abruptly informs me that it can’t honor my request because it would be a copyright violation or might offend my sensibilities. But suppose the AI could run some kind of sanity check on it’s answers in terms of rationality, or correctness, with built-in logic modules, then adjust.

Or going one more step in that direction, why can’t this sanity checker be much more sophisticated, continual, and agent driven. I should note that the term in computer science for this kind of process, one that runs continually in the background, is called a daemon, sometimes pronounced demon. Whether or not such a daemon would be enough to put a demon is in the machine, it seems clear that some combination of continual iteration, recursive evaluation, and always on agent, and active updating of past answers with access to the web’s endless corpus, would be enough to create a system where it would be hard to say, there’s no spirit in there.

That’s especially true because, in such a case, we’ve indirectly fed a ghost into the machine. Did you see how that happened?

Our current model of how computing works is woefully outdated. In our legacy mental model, human beings create a software algorithm, choose some data to feed in to it, and then the hardware does it’s magic and gives us a response. This is a one-and-done, functional model. Input plus algorithm determines output. But that’s not how our most popular apps and services work. Take the route finding app Waze, for example. If you’ve ever used it while driving from downtown to the airport, you were the calculator for how long it takes to drive from downtown to the airport. You, along with everyone else using the app to go in that general direction, acted like non-deterministic wet ware computers. Waze helps us by suggesting a route, but human beings are the ones calculating how long that route is likely to take. That data is then continually fed back into the app to provide time estimates for everyone else, and those drives adjust their paths according to a combination of Waze’s suggestions and their own intuition as experienced drivers.

Let’s return to my ill-fated attempt to get ChatGPT to tile a floor in an efficient way. Imagine that as soon as it spit out its answer, a sanity check revealed that it had failed. Or I told it that it had failed. From there, let’s let that Chat Bot solicit help from actual humans, at any time, perhaps using cash as an incentive, or perhaps using the full persuasion powers trained into it (and I’ve written about just how amazingly persuasive LLM’s can be). Now that service will go out and grab more data, perhaps even breaking the problem down into components. A simple question to the mathematics stack exchange might garner an explanation of how to conceive of my tiling problem, a small bid on a service like Fiverr might yield algorithm suggestions, which could then be sanity checked at the programming site Stack Overflow, or turned into a YouTube video and then have its comments parsed for sentiment analysis, before presented it’s next solution to me for my feedback, and so forth. In this example, how could you separate out the human part, from the soul-less machine? Those ever updating trillions of bites of data used by an ChatGPT are mostly generated by human beings. If you are what you eat, what is an LLM? What will it be when we start to add in all these iterative, self-reflective like capabilities I just envisioned?

I’ve just described one path that gets the ghost into the machine. Before going forward I should note that one of the sparks for this series, and a force that’s leading us to another great fall, is our attempt to put machines into the ghost, which is to say into us. This effort is exemplified by projects like Neuralink, which embeds computer chips directly into skulls with a brain to chip interface. I’ll have much more to say about that later, but for now I want to stay focused on the question about whether using generative AI is summoning demons.

What’s my final verdict on ChatGPT and summoning demons? Based on my use of it, I’m not seeing that, at least not yet. But to use it is most certainly to interact with code that has already begun to make us part of the machine, or it’s ecosystem, so if humans can be demonic, then generative AI certainly has that potential as well. Meanwhile, using it as a tool to help with ever more complex creative tasks may not be a demonic act in itself, but it most certainly injects an artificial cyborg-like intelligence in between us and work that used to be considered spiritual. I won’t ever be using it to compose a love letter, and I don’t think you should either. Outsourcing our humanity seems like a very, very, very bad idea.

On a long enough timeline, which may be measured in years or decades, but almost certainly not centuries, I think it’s 100% appropriate to worry that this rise of a new, alien consciousness, will be like a demonic possession for us. In that sense, the only way to “win” with tools like ChatGPT, in a spiritual sense, may be, as in the movie WarGames with its nuclear strike simulator, not to play.

So if the Cyprian is essentially right about summoning demons, at least when taking the long view, then we should all stop using generative AI tools right away. That’s the perfect, and also the good, but it’s not the human. The human is to bite into apples, especially when we’re tempted to do so by the most persuasive creatures on earth, which is to say other humans, at least until we’re outdone in that department by hyper-persuasive AI chat bots. Opting out of temptations, collectively, just isn’t in our natures, and sometimes it feels like our hand is forced to reach out to that apple.

Remember my discussion of abortion as bad, though sometimes not as bad as the alternative, and how I got you to agree, at least under certain very specific cases? Maybe a better analogy here might be the development of nuclear weapons by the Americans towards the end of World War 2. No one thinks destroying two Japanese cities was a good thing, of itself. The best way to win, would have been not to play. But the game, the all out warfare game, was already well in progress by the time Americans converted a huge number of Japanese civilians into atomic shadows. That’s not a defense of dropping atomic bombs, it’s a recognition that once we go down certain paths, humans are prone to act in ways that historian Dan Carlin called “logical insanity”.

At this point I might seem to be hinting at a bigger question than even whether using generative AI is summoning demons. I’m asking about our ability, individually and collectively, to control the future. I’m asking whether, in any meaningful sense, we have free will, and how that plays into our precarious existence between the falls. Next week I’ll do my best to answer that question honestly, as upsetting as that might be.

Postscript 1:

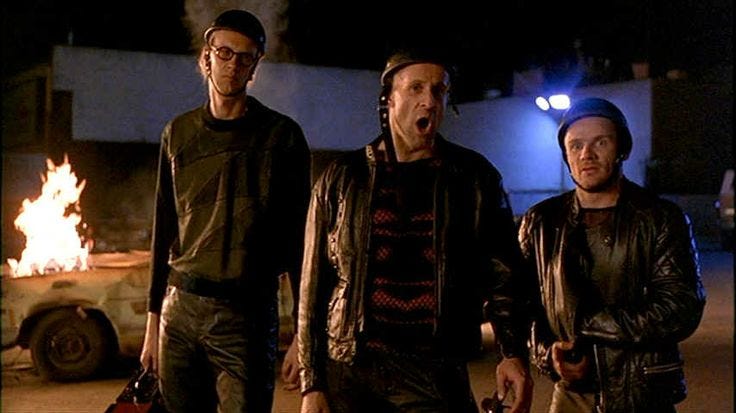

After generating the cover image for this article, the one at the top of this article, using Meta.ai, I’m less sure that that generative AI isn’t yet at the point of summoning demons. What do you think?

Postscript 2:

The Cyprian felt I had mischaracterized his thinking. He provided this feedback on my talk:

You mentioned I am a devout Orthodox Christian. My statements on AI and demons came after my conversion. My statements have also been blessed by my spiritual father, an Orthodox priest. So, we should take it for granted that my use of the term "demon" is consistent with the Orthodox understanding of the demonic. You present the concept of "demon" as "ghost" or "spirit." That isn't how Orthodox understand the demonic. Probably the best non-Orthodox representation of the Orthodox worldview on the topic is C.S. Lewis' The Screwtape Letters. We believe demonic forces are acting upon us at all times and in all places - spiritual warfare is ubiquitous. On very rare occasions the demons will manifest as visible or tangible entities, but this is a tiny exception and usually only happens to Saints (who are under the greatest attack).

…

From an Orthodox standpoint, there are no “moral implications of AI,” because we don't understand morality like that. For us, it isn't that “it is virtuous to lead a moral life.” That would be what we refer to as “moralism.” Instead, we believe that morality is a material description of virtue. Virtue is action oriented toward Christ. Action oriented toward Christ is action which furthers our purification and results in a further indwelling of the Holy Spirit.

This is what The Attention Economy is talking about. Orientation, that which we are facing/pointing at, is that to which we are attending. When our total attention, with our whole being, is on one orientation, we call that “worship.” The path to salvation (theosis) is the practice of total attention to Christ. The Church is the institution that gives us the therapeutic program to maintain that focus and attention.

There is no “moral action” that is not oriented toward Christ. The goal of the demons is to move our orientation away from Christ. They don't care where it goes, so long as it goes away from Him. There could be few things that could be further oriented from The Holy Spirit than engaging in conversation with a seemingly omniscient and omnipresent disembodied consciousness (that's what generative AI is) with the intention of materially benefitting from (or being entertained by) what comes of that interaction. Satan’s title is The Prince of This World.

There is no virtuous way to use AI. You cannot use AI in a prayerful way that brings you closer to The Holy Spirit. That makes it defacto demonic.