(This is the seventh post in a series about our precarious existence “Between the Falls.” If you haven’t read any of the previous ones, you might want to go all the way back and begin with the first, which explains the idea behind this series, but here it is in a nutshell: technological progress and the move towards transhumanism have us on the precipice of a second great fall of man, the first one being that famous, symbolic or literal, bite of apple that drove us out of our primal state of ignorance and grace. In this post I walk through the Uncanny Valley, exploring the moral challenges that come from our increasingly frequent interactions with the not-quite-human. I don’t want to give too much away, but there will be talk of power tools, real dolls, doormen, hyperreality, and aliens in skin suits.)

I remember first hearing about the concept of the uncanny valley when the movie “The Polar Express” came out. It’s done in a style of animation that’s almost, but not quite, realistic, and probably as good as was possible 20 years ago. The characters had a weird not-quite-human look. I remember one critic said they had “doll eyes” and looked “dead inside.” Which is a description that makes sense to me, though you can judge for yourself from the main image for this post.

The term “uncanny valley” was coined to describe that place of not-quite-humanness that is the realm of zombies, real dolls, and aliens in skin suits, like when the intergalactic bug in “Men in Black” puts on the flesh of ex-farmer Edgar. We humans find Bugs Bunny charming, and our fellow humans compelling, but somewhere on the road to realism, but before arriving, you’ll end up passing through a nightmare chasm, a place of literal monsters. Whether or not you make a left at Albuquerque.

I’m going to argue that this chasm, and the feeling of eeriness it provokes in us, serves as a warning to us, a gut-check that something more is going on that just the commission of an aesthetic sin. It’s a signal that we may have transgressed into a place of spiritual wrongness, a desert of the soul that we should be very careful about crossing.

Shell game

In a series of podcast episodes called “Shell Game”, Evan Ratliff slowly hands off the tasks of his life to an AI trained to replicate his voice, with access to his personal data and biography. My favorite moments are when his AI is talking to friends or co-workers on the phone, and the other person starts laughing uncomfortably. They realize something is wrong, but not always what. Having a conversation with AI Ratliff is a disquieting, slightly disturbing experience. The AI speaks just a bit too fast, without the appropriate emotive range, and its pacing is too uniform. AI Ratliff is too sterile, always upbeat yet flat, incapable of conveying actual depth of emotion or thought. Which makes sense, of course, because AI Ratliff is not quite human, which is to say, not human.

I should note that humans themselves often act in ways that are “not quite human,” or at least highly scripted. The reactions people had when talking to Ratliff’s AI reminded me of an unsettling moment I had with a high school girlfriend. Based on some contextual trigger I can no longer remember, she felt compelled to make sure I understood that the proper order of operations for dealing with stuff was “reduce, reuse, recycle,” which was one of the bits of ubiquitous eco-propaganda floating around at the time. There was no discussion to be had about it, she just needed me to acknowledge receipt of the cliché she was parroting, and got upset when I didn’t immediately echo it back, like I was a homeowner who for some reason wouldn’t sign for a package the UPS driver had just handed to me. Her insistence on repeating the same phrase over and over until I “got it” felt creepy. If we had this expression back then, I would have said she sounded like a scripted NPC — humanlike, but not quite human.

There’s another, much less charitable word for fixated NPCs and unconvincing chatbots: defective. Besides laughing uncomfortably, a common response to Ratliff’s AI was to ask if it was okay. As in, Evan, why are you acting so strange? So broken? Are you alright?

FetLife

Let’s talk about fetishes. And I don’t mean in the colloquial way that word is often used, as in enjoying kinky sexual practices. I’m using it the deeper, much more pathological sense. If you’ve ever been around a true fetishist, the experience can be disturbing. Imagine a guy who just will not stop staring intently at a woman’s feet, even when they are having a conversation. He’s completely obsessed with the object — the person that object is attached to is irrelevant.

The fetishist lives in a world where items are elevated to the primary focus of attention, reorienting relationships away from people. Human beings are necessarily debased by comparison, and often this debasement itself is part of the kink. Objectification is a feature, not a bug. It’s hot. The people who do this are properly called creeps, a highly usefully word that sadly seems to have left our lexicon.

How to talk to your chatbot

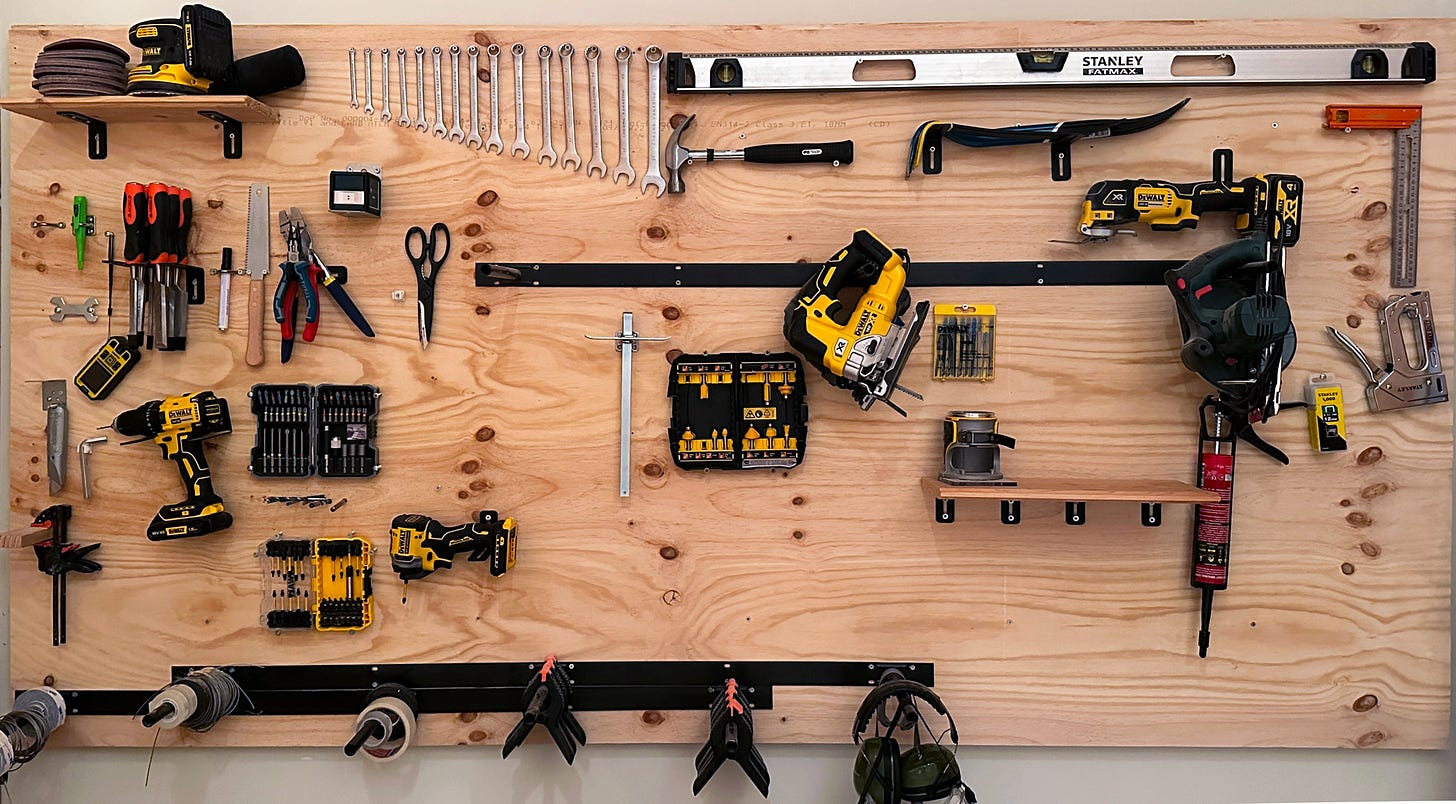

Shown above is a photo of a tool wall I created towards the beginning of a renovation project for our home here in Amsterdam. That’s still on ongoing project, and I am continually taking tools off the wall, using them, and then mostly putting them back where they were, often a bit dustier and more scraped up than when I took them down. I feel bad when I occasionally break a jig-saw blade or a drill bit, but only because that costs me money and is a hassle to replace, not because I’ve harmed the tool. All those black and yellow 18V cordless DeWalts are just tools — they require proper handling, but no niceties or apologies. I feel no need to be polite to them.

My twin boys are now 2, so for them, reinforcing polite behavior is a big part of parenting. Once they are a bit older, they’ll demand to know why social niceties like please and thank you are so important. I won’t struggle to answer. That’s obvious to me. It’s a key part of acknowledging the humanity of the people you are talking to, and letting them know you view them as souls with agency, who can choose to do nice things for you voluntarily. Or not.

While chatting with OpenAI and other LLM’s, I often find myself debating whether I should be polite, or save myself the extra typing and just demand answers in as terse a way as possible. Like my DeWalt tools, these models have no souls or feelings or agency. They aren’t spiritual creatures who need to be treated in a certain way for moral reasons. And yet, I still think it might be a good idea to treat them as if they were human.

The problem with entering an uncanny valley filled with not-quite-human creatures is that you are, to some extent, forced to choose between three modes of interacting with them, each one morally suspect in its own way. The reason I choose to treat a chatbot less crudely than a DeWalt is not for its sake, but for mine. Social niceties aren’t just about respecting the person you are talking to, but also about expressing our own humanity. As in, even if you know an old lady won’t acknowledge or even appreciate you for holding a door open for her, you should still do it, because it’s good for your soul. Conscientiousness is a habit, a practice. Best to keep that practice up, right?

On the other hand, treating the non-human as human, or elevating it to that status, puts me in a position that’s uncomfortably close to the fetishist. I’m not interested in having a relationship with my chatbot. I really appreciate my black-and-yellow DeWalts, but at the end of the work day they go back up on the wall, and at no point would I choose spending time with them over spending time with my family, beyond what’s needed to build the things I want to build.

The more we view our AI interactions as human-like interactions, the more we’ll be tempted to use them as a substitute for actual human interaction. Being polite to them is a part of this. That’s a basic part of human psychology. When we care about something, we tend to treat it with care. But the inverse of this is also true. The things we treat well, we tend to grow affectionate for. If I got into the habit of mindfully cleaning off my hand tools after each use, and placing them on the wall with two hands and a bow, the way the Japanese always respectfully give out business cards, I would probably develop a higher degree of affection for them. I might even start to treat them like the sergeant in “Full Metal Jacket” wanted his soldiers to treat their guns.

It’s hard for me to imagine a more dystopian scenario than widespread bonding with AI’s as a substitute for actual human relationships.

So what about the third option? How about we treat chatbots exactly like the not-quite-human entities they are? This is, I suspect, the path I’m headed down, and many others are too. It’s a meet-in-the-middle strategy, where we treat AI agents with more consideration than a calculator, but less than our neighbors. We actually may not have a choice but to adopt this strategy, since interacting with these agents often means altering our communication styles to be more intelligible to them.

Meeting in the middle

Maybe you’ve had the following experience with a voicemail bot. A female sounding voice asks you to state your problem, and you begin by provide a detailed description of what’s wrong. This it can’t parse at all, or it misunderstands your words, and decides you need something completely different from what you asked for. So on your next attempt, you oversimplify, and say something like, “TECH SUPPORT”. Unfortunately, this leads not to a human who can help you, but to the follow-up question, “Ok, I understand that you need tech support. What do you need tech support with?” Finally, after much frustration, you figure out how to tailor your interaction to the bot, and shout at it in a robotic voice, “HELP WITH BROKEN INTERNET CONNECTION.” This works and you are routed to an actual human, who may or may not be able to help you.

This way of interacting may seem like a small frustration, but being forced to dehumanize yourself in order to meet the bandwidth limited, NPC like, robotic AI assistant at its level, that’s not good. In this transitionary phase, when chatbots are good, but not human-level good, we’ll be spending a lot of time drawn into the realm of the uncanny valley. In this realm, we’ll get into the habit of interacting with things in a way that’s not quite human, but also not tool-like. Meeting a simulated human in the middle doesn’t seem like a win, and in some ways might be the worst of all options, because it encourages the bad habit of intentionally acting dumber and coarser. This would be the equivalent of opening the door for that old lady, then turning to her and yelling “PASS THROUGH THE DOOR,” then abruptly closing it behind her as soon as possible. Functional, efficient, soulless. Way creeper than a motion-activated door or, of course, a real doorman.

Surrender to the simulation

Every now and then, it’s worth noticing just how much of our current reality is fake, or simulated. Of course all our digital interactions are on symbols designed to invoke real world analogies, like our file folders and trash icons. There’s no way to use a computer otherwise, unless you speak binary with the skill of an AMD Rizen 7 chip, which of course you don’t.

But even outside of interactions with the digital, which takes up an ever greater chunk of each day, things have become less real. Our “meatspace” is built with fake wood floors and fake brick facades. We sit on couches made of fake leather with simulated rawhide texture. We eat in restaurants with fake rechargeable candles on our laminate tabletop and fake plastic plants in the corner, after being seated by a hostess with a fake smile. Fake metal trees hide 5G cell towers, and simulated RPM and MPH needles fill out our car’s dashboard screens. We live in a world of things made to look like other things that used to exist in the past.

What does it do to us to spend all our time in a world where everything is a cheap fake, a shallow replica, an AI pretending to be a receptionist, a news report written by an unthinking journalist and then summarized to us by a digital assistant?

My fear here is that we are getting sucked in the uncanny valley whether we want to be or not, and at least during this time of not-quite-humanness. At some point, the underlying referent gets lost, just as I can no longer remember the last time I saw a real phone handset that looked like the phone icon on my iPhone. And just as in the phone to iPhone swap, these voids are being replaced with something more compelling to us.

Right now we are disconnecting from reality, free-floating into an eerie abyss, or what James Baudrillard called “the desert of the real,” which you might recognize as a line from “The Matrix.” It’s a concept that, along with the idea of the simulacra as “truth that hides the fact that there is none,” took me a long time to really grasp, until I understood that Baudrillard was talking about a world in which there’s nothing behind the curtain, which is a perfect analogy for expression “the lights are on but no one is home,” which itself is exactly how those dead-inside animations from “The Polar Express” present.

As the desert of the real is extended, we see the rise of what Baudrillard calls hyperreality, which to me looks like the land on the other side of the uncanny valley, or the place we’ll spend all our time after the next great fall of man.

In hyperreality our simulated, or augmented, worlds will be so compelling we’ll never want to take off our AR glasses. Unbounded by the limitations of the real, once we surrender to the hyperreal, we’ll enter into a garden of delights that makes smoking crack seem like a green tea caffeine buzz. Our real dolls will be so much better than human partners, in so many ways, and we’ll able to customize them “Total Recall” style, with as many breasts as we’d like. Or with a tail. And horns. And red skin.

The Animist Antidote

As I’ve laid things out, no matter how we react to our forced interactions with the not-quite-human, there seems to be no way to emerge with our humanity intact, at least with our current understanding of the term humanity. We must be debased or debase, which is itself debasing. The only way to “win” seems to be not to play. But try telling that to to the AI voice assistant when you call your telecom for help with a service you absolutely must have. Unless your plan is to put on a straw hat and join the Amish in rural Pennsylvania, you will be playing this game.

I’d like to hold out a ray of hope in the form of a “the only way out is through” solution, one that’s related to a highly reverential culture I already mentioned, the Japanese. Shinto, that land’s indigenous religion and a strong influence that continues today, is animistic. In Shinto, objects of all sorts can have spirits. Shinto might say that I should treat my DeWalt tools with care because they contain kami, spiritual essences that need to be properly respected, or even revered.

Animism, if carefully built up with layers of reverence, might be a way to treat the inanimate as spiritual, without diminishing the humanity of actual people. This is similar to how panpsychism, which posits that a kernel of consciousness exists in even the smallest particles, integrates rocks into a continuum with humans without diminishing our own consciousness. As animists, perhaps we can approach the uncanny valley with a certain discernment, and recognize manifestations of not-quite-humanness as malevolent spirits, or ara-mitama, that need to be cleansed from our world. The uncanny valley is a land filled with demons who must be excised.

That said, Japan is also ground zero for the embrace of creepy sexual fetishes, gadgets, and all things digital. As their population slowly declines they are, by necessity, handing off elder care to robots. Loneliness is so endemic that you can rent an old retired guy to hang out with you for the day, which says something about both demand and supply. So perhaps animism, or at least Shinto-flavored Japanese animism, isn’t the best way to handle our slide down the cliff into the uncanny valley.

Is there another way out that involves going through? Maybe it’s time we finally put on the headset.

Very nice! We've been writing an extensive series on similar topics (e.g., hyperreality) from a different angle, which you might enjoy. e.g., https://bewaterltd.com/p/the-death-of-the-real