BtF 4: Mimesis and Dark Desires

(This is the fourth post in a series about our precarious existence “Between the Falls”. If you haven’t read any of the previous ones, you might want to go all the way back and begin with the first, which explains the idea behind this series, but here it is in a nutshell: technological progress and the move towards transhumanism have us on the precipice of a second great fall of man, the first one being that famous, symbolic or literal, bite of apple that drove us out of our primal state of ignorance and grace. I don’t want to give too much away about this week’s talk, but it will involve frozen bodies, Weird Al Yankovic, Muammar Gaddafi, Turkish gunslingers and gimp suits.)

I was planning to talk about the headset theory of consciousness this week, but I got distracted by a Chinese girl biting her Olympic medal and realized there’s a different topic I should talk about, one that follows perfectly from last week’s discussion of string theory.

Maybe you’ve seen that photo, or sequence. Two Italian gymnasts standing at the awards podium bring their medals up to their mouths to strike a cheeky pose that would have made sense back when Olympic medals were actually made of precious metals. The third woman at the podium, a Chinese gymnast, notices how the other two are posing, looks confused for a moment, then timidly brings her own medal up towards her mouth but can’t quite bring herself to put her teeth on it. It’s a charming little scene, and anyone who isn’t well out on the spectrum gets it, and can empathize.

Human beings are imitative creatures. When uncertain about what to do, we imitate the people around us, even if we don’t understand why something is being done. But it goes even deeper than that. We also copy the desires of others. Beyond our inborn drives for food and water and sex, we tend want what the people around us want. Often that means the exact same object. As the father of twin boys, I can confirm the experiment where you buy two of the exact same toy, and your kids will end up fighting over a single one of them precisely because the other child has it.

As related aside here, if you’ve ever felt tempted by political calls for equity, you might want to take a moment to consider the implication of aiming for equity in a species that is biologically wired to want not just the same big house as their neighbor, but their neighbor’s house itself. And his wife. Or a better version of each of these. Maybe the tool you want to reach for is religion, not politics. More about that in a bit.

As another, personal aside here, I spoke last week about how the key to achieving some level of free will, or at least expanding your locus of control, is to begin by recognizing the strings that pull at your behavior and desires. I tend to be fairly aware of those, but there’s also no doubt that the things I’ve wanted over the years were highly impacted by my environment, and there’s a thin line between adapting to your environment, and thoughtlessly absorbing the desires of those around you. For example, when we lived lived in the Florida Keys, I bought a mini-yacht, really a much nicer one than I should have, with dual Mercury 300 outboard engines, and I subscribed to a few boating magazines and fantasized about much bigger boats. Before that, living in Toronto at a time when everyone was into real estate, I spent thousands of hours looking at pictures on Realtor.ca, often in fantasy mode. The first property I bought there was a cottage north of the city, because that’s what everyone did. After that I ended up living in and then flipping a couple lovely homes in Toronto, which turned out well for me, in large part because the chain of desire I participated in was still going strong when I left, despite the province’s attempts to depress housing prices with additional transfer taxes and rules.

On an even more personal note, when I was much younger and living in Bolivia, I fantasized about Cholitas in short polleras shaking their hips while dancing the Caporales. Dance, of course, exists in large part to drive desire. The Caporales certainly worked for me.

The point of these memories is that, as mimetic creatures, we tend to desire whatever is presented to us as desirable. Even having an understanding of this dynamic, which I certainly did by the time I moved to Florida, didn’t immunize me against overspending on a boat that I wanted, not just to be practical, but also to stand out as a cool alternative to the center console fishing boats everyone else in the Keys had. I told the story of a boat I almost purchased during a podcast interview with David Gornoski about Girard’s Mimetic theory, and if that’s the word that’s been in your mind as I discuss imitative desire, it’s the right one. That other boat scored way higher on the coolness scale and had an amazing history of exploration linked to a semi-famous person, but it would have been a much worse fit for our shallow waters, so I had to very intentionally let my concerns about practicality overpower my desire to pick a boat just because others would have found it desirable, at least in the “oh how cool you have a DeLorean” kind of way.

As should be clear from this last example, another way to reframe mimetic desire is to note that we all crave status, and status is often based on the extent to which the things we have are also things that other people want.

This form of mimetic desire naturally induces a hierarchy. In centuries gone by, living in small communities, people mostly had a single place in this hierarchy. Their status was tied to their job or caste, and to a limited extent that person’s individual, perceived character. These things were hard to change and likely viewed the same way by everyone else in the village. Think of how if someone went to a small high school, they could rank the boys or the girls by popularity, and their own raking would be nearly identical to the rankings made by everyone else in their class. A single consensus existed about status rankings, and this meant one could only gain more status by “dethroning” someone above them.

As we near the end of the current human era, and approach our second great fall, the number of ways to gain status has grown exponentially. Not happy with your current level of social status? With enough effort, you could become the queen of cross-stitching, an admired Magic the Gathering player, a highly followed fan fiction author, a Tik Tok influencer, or a YouTuber who got to a million subscribers by filming dumb pranks. You could get props just by looking cool while shooting a pistol at the Olympics. This last one, I must admit, induced a brief moment of envy in me. I could have been that 51-year-old Olympian with a dad bod and a single, highly technical skill.

If there are now a million ways to get fame and respect through hard work, creativity, or luck, once we transition to the post-human future these will be available to everyone, at least virtually, with much less effort. In the 2002 movie “Minority Report”, we get a glimpse of a “Cyber Parlor” where clients hook up to immersive machines to indulge in fantasies like killing their boss or getting showered with praise. Two decades later, we now have the ability to offer these kinds of individualized, multi-sensory experiences in ways that are nearly as compelling as the ones depicted in the movie.

On the one hand, this is an amazing tool that solves a fundamental dilemma of humanity, how to reconcile our mimetic desires with scarcity of resources and status. In this brave new world, without the use of force, I can experience the feeling of having my neighbor’s house. And his wife. And maybe he’s at the foot of the bed in a gimp suit watching us like the little cuck I’ve always suspected he was.

So obviously this can get dark, right?

Religion has been, historically, the big solution to the problem of mimetic desire spilling over into dark thoughts and violent behavior. The old testament gave us the Decalogue, with its commandments not just to avoid certain actions like theft and murder, but also some desires as well. Don’t covet your neighbors ass, or his wife’s ass. That’s a sin and God will surely punish you.

Christianity solves the problems of mimetic desire with love not fear, and with the promise of role reversal in the great beyond. Instead of coveting what your neighbor has, love him as if he were you. Also, the victim is sacred. The meek and repentant will one day rule for all eternity. That asshole next door with the bigger house and prettier wife? In the words of Weird Al Yankovic from “Amish Paradise”:

I really don't care, in fact I wish him well

'Cause I'll be laughing my head off when he’s burning in Hell

Of course this is parody and exaggerated, but it is part of how religion can encourage us to let go of our naturally covetous natures. No need for violence now, I’ll get my just dues in the afterlife.

But what if we could find a secular solution to the downsides of mimetic desire? Beginning roughly four centuries ago, humans invented an economic system that did just that. Free market capitalism is a powerful tool for aligning mimetic desire with virtuous action. In a free market, the way for you to get a better car than you neighbor is to make more money than him, and the way to make more money is to provide greater value to others. The better you are at offering products and services other people want, the more capital you accumulate.

This is, of course, a highly simplified and idealized story. But we’ve seen it play out just like this, especially in the early stages of a transition from a mercantilist or command economy into more of a free market. People got richer, they died less often from dysentery or choleric deficit. That’s a really good thing.

Over time, all kinds of less-positive side effects tend to spill out from economic freedom, including rent seeking efforts and other bad behaviors that alter or poison the system. For now let’s just recognize that as things are right now in the West, our economic system is partially aligned with virtuous actions, and I’ll let you come up with your own estimate of how partially you think that is, but clearly it’s neither 100% nor 0.

Regardless, our system has been really good at driving down the cost, in terms of both gold and bloodshed, of satisfying our human desires. But what happens to our society as we begin to invent virtual ways to experience wealth and status at real world costs that are trending down to zero?

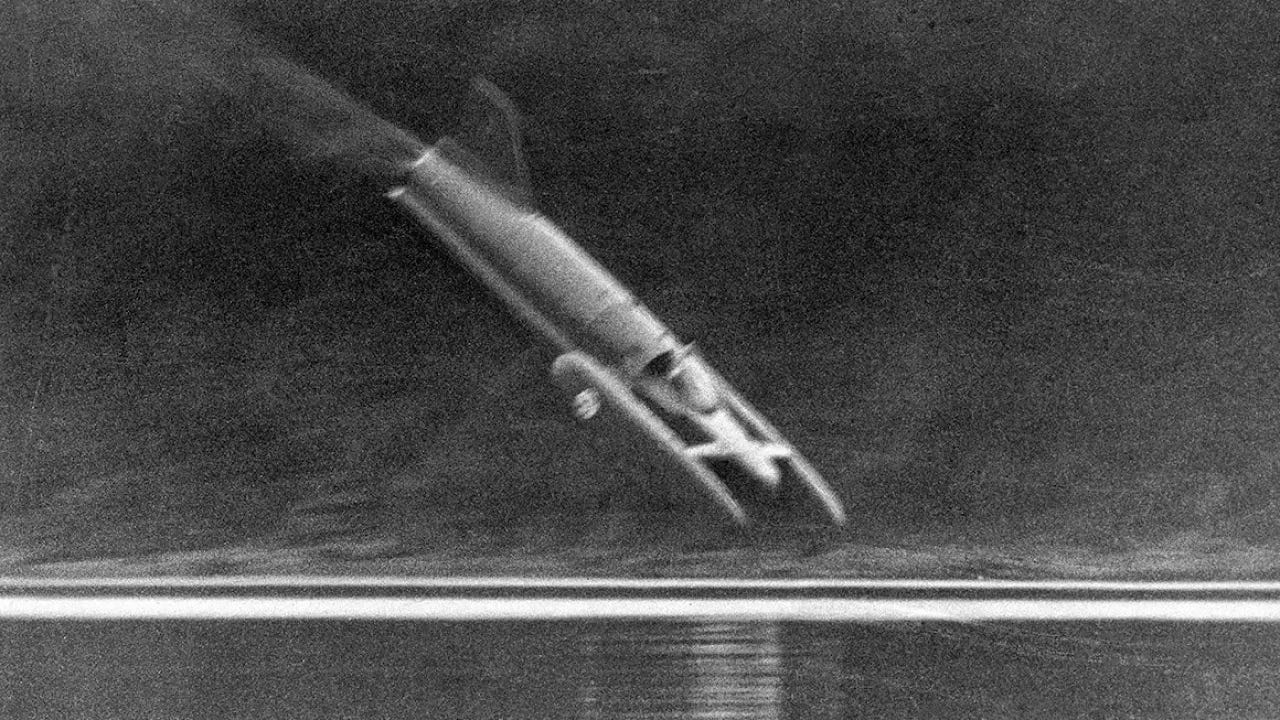

A dark side of mimetic desire in the face of economic and status scarcity is that it drives violent conflict and political repression. But it also drives us to excellence and achievement in the face of risk. Consider for a moment the history of the water speed record. Of those who’ve made a serious attempt at breaking that record, about half have died in the attempt. Despite those miserable odds, you see individual competitors who pursued the record over a long enough timeline to to win, lose, and then regain it. You even see an intergenerational example of this, with a son who reclaimed his fathers record, then died during an attempt to extend his lead.

Or consider the efforts made by those attempting to summit Mount Everest. Not only do these climbers have to commit about $100,000 for the attempt, their path will take them past dozens of frozen bodies of men who died trying to do the exact same thing, a not so subtle reminder of the risks involved. Note that in a sense those dead bodies are a feature, not a bug. When it comes to quests for valor, which is to say attempts to turn mimetic desire into achievements that others will come to envy themselves, a high level of risk both adds to the level of valor, and serves to keep the club exclusive.

After the next great fall of man, when we’ve gained the ability to offer virtual experiences that are indistinguishable from the real thing, anyone will be able to experience the intoxicating thrill of summiting Mount Everest, or speeding across a lake at 400mph to win the crown of fastest man on water. Anyone who wants will be able to break open a virtual champagne bottle next to a gaggle of admiring groupies. All with zero risk of turning into an ice statue on Everest, or sinking to the bottom of Lake Havasu.

This is both an amazing advance, and also has the potential to be the most addictive drug imaginable. We often view our current moment as some mix of Orwell’s “1984” and Huxley’s “Brave New World”. If “1984” represents the stick, the boot on the head demanding eternal obedience, then Brave New World is the carrot. The drug that lulls users into a state of peaceful acceptance, no matter how miserable their lives are on the outside. It’s OASIS in “Ready Player One”, or aspects of the matrix in “The Matrix”. It’s a virtual world where you can bite into a juicy steak while seated across from a blond in a red dress, so long as your in-game credit score is high enough. Which of course is exactly how immersive virtual worlds could become tools of social control that exceed anything we could possibly imagine right now, in large part because they make these experiences way less expensive, at least in terms of direct monetary costs.

One of the things that made the crack epidemic so horrific was how accessible the drug was. I’m too young to speak from personal experience, but I remember how in the 80s cocaine was a rich person’s drug. Something for businessmen to use in the bathrooms of fancy nightclubs with bottle service, if that was thing back then. Cocaine was the drug that about-to-be-millionaire Len Bias blasted his heart with to celebrate becoming the second pick in the 1986 NBA draft.

Crack became so much more destructive than pure cocaine in large part because it was so cheap, the kind of high anyone with a minimum wage job or a welfare check could afford. I did get some personal experience with the effects of that drug while living in Chicago in the early 90s, and spending time in a many of that city’s worst neighborhoods. I saw how crack, along with horribly distorted economic forces, turned those places from merely poor, to violet hellholes.

I’ve argued that the free market has the power to align human desires with virtuous actions. I also noted how this same economic engine, the one that allowed us to double lifespans in a couple hundred years, has the ability to drive down the costs of our vices to almost zero, and provides economic incentives to invent ever more powerful temptations. You’re already getting a taste of this with whatever mobile app you find most addictive. How much does one more hour of scrolling through Tik Tok cost you? Only your life force, right?

There’s another dynamic in play here, as we slide down the slope into our post-human future. Another side effect to mimetic desire, or perhaps a related piece of our human nature, is that we enjoy the immiseration of others. This is, for sure, not true about everyone, and certainly not all of the time, but there’s no lack of historical evidence for this very dark desire. Torture of the enemy is a feature of just about every indigenous culture we’ve come to understand at a deep level, and torture of the condemned drew popcorn-chewing crowds throughout much of European history. If you have a strong stomach, you might want to check out Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History episode titled “Painfotainment”.

In the modern West, we’ve largely managed to channel our desire for the debasement of others into less brutal acts. But the desire itself hasn’t left us. It still seems particularly pronounced in our political class, with its overrepresentation of narcissists and sociopaths. Recall Hillary Clinton’s 2011 comment when asked about Muammar Gaddafi, who was sodomized to death with blunt objects after America intervened into Libyan politics. “We came, we saw, he died,” Clinton said, with a cackle of joy.

In my last post, I wondered in what ways the next great fall of man will be managed, and to whose benefit. Given the high degree of sadistic tendencies among our elites, there are some very real dystopian possibilities here.

As I’ve described, Christianity, and then capitalism, have served as ways to reduce, or redirect the dark side of mimetic desire. But as we edge ever closer to our transhuman future, I worry that this one-two combination may leave us unprotected against demonic elites who, thanks to technological advances, have ever more power tools for using our mimetic desires against us, for their profit, or to cackle in delight at our own debasement, “Hunger Games” style.

Next week I’ll discuss the the need for a new tool for managing our mimetic natures, one that’s very different from our current religious and economic systems, if we want to avoid absolute rule by sociopaths, which I certainly do. I’ll also discuss one more related piece of the puzzle in terms of understanding how the next great fall of man might play out: the connection between interconnection, and mob rule.