BtF 3: String Theory

(This is the third post in a series about our existence “Between the Falls”. If you haven’t read any of the previous ones, you might want to go all back and begin with the first, which explains the idea behind this series, but here it is in a nutshell: technological progress and the move towards transhumanism have us on precipice of a second great fall of man, the first one being that famous, symbolic or literal, bite of the apple that drove us out of our primal state of ignorance and grace. I don’t want to give too much away about this article, but you will find talk of pachinko, smelling smoke, conspiracy boards, Huma Abedin, and how to be master of your own domain.)

I’d like to talk about a different kind of string theory.

I’m going to begin by discussing a belief that I really dislike, and maybe you do too. It’s the idea that free will is an illusion. This may seem like a detour away from the central theme of these talks, but I promise to tie all the pieces back together. Or at least to try. We’ll see how that goes.

There are a handful of topics that seem to bring out the dumbest arguments from people who are generally regarded as smart. Politics, of course, is one of those topics. As is anything that falls into the category of an “unexplained phenomena”. Also, and perhaps not surprisingly, the abilities of the human brain itself seems to be one of those topics. Several actual geniuses from the last century, including the great Alan Turing himself, argued that computers were capable of everything our minds could do, because if you described a mental process in the form of a well-defined algorithm, he could implement it in computer code. If it’s not clear why this is a dumb argument, imagine I argued that spoken language had more expressive power than written text, and your counter argument was that you could write down any combination of English words I said out loud. Do you see the problem?

One of the most common dumb attacks on free will is to demand to see the place where the free will occurs. A big thinker will say, OK buddy, so where does that magical free will reside? We’ve modeled human brains. We’ve dissected them. Nowhere do we see the “free will mechanism”. It’s just chemistry all the way down.

Of course, the same could be said of consciousness as well. Sure, we know there are parts of the brain that impact consciousness, but where does the self-reflection “piece” live. What gives rise to it? Can we really believe it exits without an explanation of how all that chemistry produces it? The answer is that, of course we can. We experience it directly. I don’t need a demonstrated mechanism to prove consciousness exists, because I have it.

We seem to experience free will in the same direct way, but could that experience be a mirage? I’ve heard cartoonist, pundit, and public intellectual Scott Adams make this argument on his CWSA podcast. Describing an experiment where high-powered magnetic waves, when pointed at animal brains, are able to alter behavior in predictable ways, Adams said that once we show that human behavior can be controlled in the same way, we will understand that free will was always an illusion. Much respect to Mr. Adams, but this is a really dumb attack on free will. It’s no more valid than saying we can’t have free will because if I throw you off a cliff, I can predict with 100% certainty that you will decide to plummet to your death. Where is your free will now, Flat Stanley?

In a less extreme way, people respond to incentives, often in completely predictable ways. I have no interest whatsoever in cleaning your house, but if you paid me ten thousand dollars an hour, I’d be there in a heartbeat with a dustpan and a mop. So where’s my free will now?

Bad arguments aside, there may be value in assuming we lack free will, at the very least in certain contexts. Scott Adams also likes to argue that we have our opinions assigned to us, generally by the media. Having seen how the vast majority of people take in the ideas and narratives they are exposed to without the least bit of critical thinking, this strikes me as largely true. It seemed especially true during the pandemic, when millions of people were hypnotized into believing that any challenge to the Covid regime policies could be trumped by saying, “You just want grandma to die!” Not only did people allow their opinions to be assigned to them, they guzzled down and barfed right back up the stupidest of catch-phrases with zero resistance.

I don’t think my own opinions have been assigned to me, but maybe I’m wrong? Either way, I find it a useful to assume that my free will is at the very least limited and subject to forces outside my control, and then I can go about understanding the ways in which I might be confusing my own chaos and reactivity for autonomy. Maybe, no matter how much thinking I do before acting, I’m really just a pachinko ball that would look like it’s deciding on its own path downward if you hid all the pins from view.

Let’s move on from pachinko to Pinocchio. In case you didn’t grow up with that story as part of your culture, or you’ve forgotten, Pinocchio was a wooden puppet, a marionette. His great desire was to someday become a real boy. His story is about his journey of transformation, from controlled, to self-controlled. From puppet to master, at least of his own domain, which may or may not mean in the Seinfieldian sense as well.

A precondition for Pinocchio’s journey to free will is that he had to actually notice the strings. He couldn’t be a real boy acting autonomously until he realized how he was being controlled, which of course makes sense once you think about it. But, also, looking for strings can be a dangerous exercise that can temp you into paranoia.

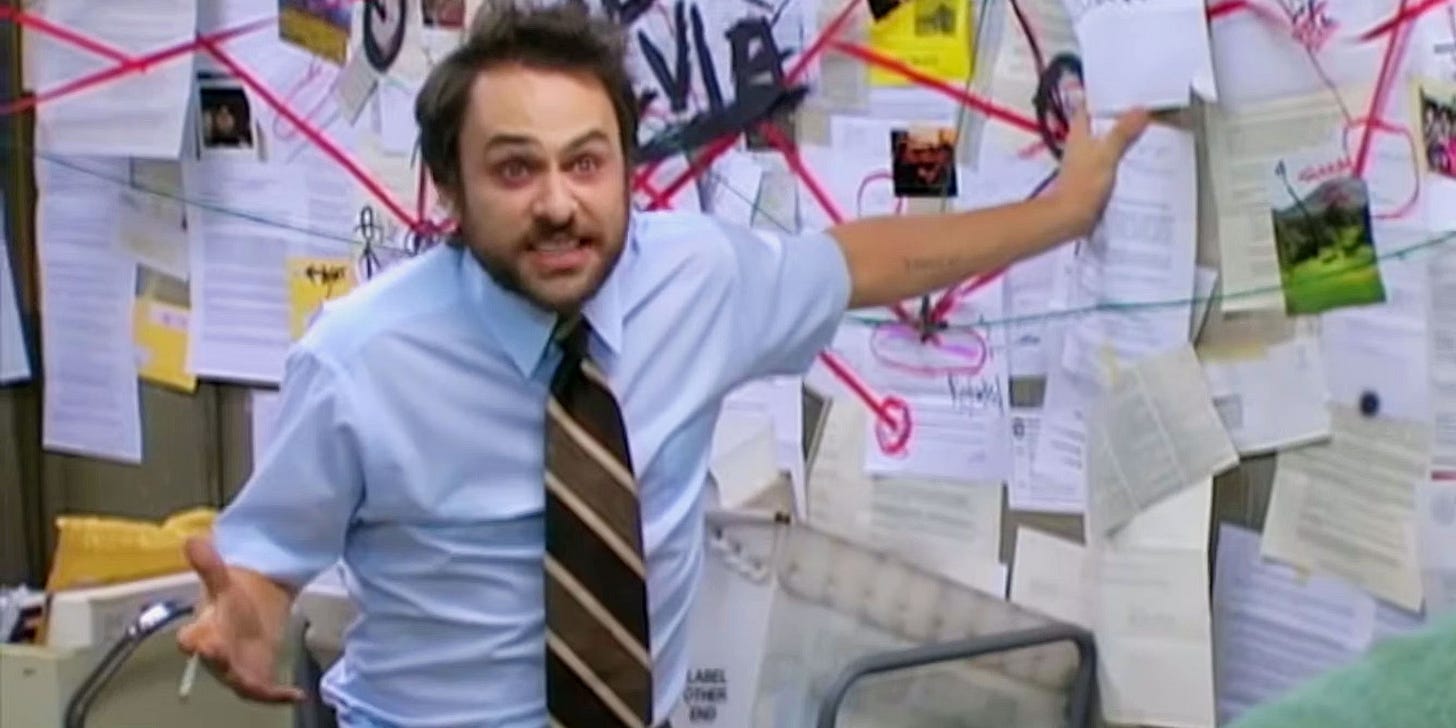

To intentionally mix strings-based metaphors, if you look too closely for hidden mechanisms of control, you might end up like that meme of the crazy guy who’s strung together pieces of paper on the wall, highlighting a web of links that his overactive, paranoid imagination has conjured into existence.

If I start to think I’m living in a controlled environment that’s being manipulated in order to influence my behavior, or simply to present me with some kind of customized experience, then am I seeing real strings attached to myself and others, or am I inventing imaginary connections that show up as strings on my “conspiracy board”? That is, to some extent, a question I’ve tested in the past with an experiment I ran, which I’m sure I’ll talk about at some point.

Meanwhile, focusing directly on what is for sure the nature of our world, it’s worth noting that a lot of the things around us that look like organically arising events, or the result of simple chaos, are clearly planned, or at the very least managed, by powerful interests. That’s not a “conspiracy theory”, a stupid term if ever there was one, but a simple recognition that people with power, like everyone else, tend to act in ways that are self-beneficial. Often, members of an elite ruling class have shared interests in certain things working out in a certain way, and take actions to make that happen. And if that idea triggers you, it may be worth considering who benefits from your brain shutting off when this topic comes up.

There’s a great scene in one of my favorite novels, The King Must Die, when the high priestess of the Minoan Labyrinth is talking to her lover Theseus. She’s explaining that the oracles she delivers to the people are planned out, and not inspired by consuming psychedelics and letting the gods speak through her. Theseus asks her, “But how can you tell what the Holy One will say through you, before you have drunk the cup or smelled the smoke?”

“Oh,” she replies, “I don’t take much of it. It makes one giddy; one talks nonsense, and one’s head aches after as if it would split.”

Young, idealistic, blue-pilled Theseus is shocked by her answer, and presses her on it, lightly.

She tells him, “Theseus, Crete is not like the mainland. We have more people, more cities, more business to fit together. We have ninety clerks working in the Palace alone. It would be chaos every month, if no one knew what the oracles were going to be.”

To whatever extent we do or don’t live in world controlled by invisible strings, it’s indisputable that those in power attempt to manage reality as experienced by the vast majority of the people around them. And they often, but certainly not always, achieve a high degree of success with that. Just looking at American politics. Remember how sudden and all pervasive the media shift was back in late 2015 to Russia, Russia, Russia? That wasn’t organic. The Corona virus may or may not have evolved organically in the wild, but the decision to make it the singular focus of fear for well over a year, with a brief and abrupt pause for 2020’s Summer of Love, that most certainly wasn’t. And, at the risk of further dating this talk, when Hillary Clinton’s 48-year old fixer, Huma Abedin, recently got engaged to the 38-year-old son of billionaire George Soros, a guy who had been funding groups that were becoming a political liability to Democrats, there is no way to understand that as an organic love affair. The oracle had spoken, and she needed Alex Soros to tone it down a bit with his funding of overtly violet left wing groups and lawless DA’s. Best to keep a very close reign on him.

So often the things that get dismissed as “conspiracy theories” are actually just obvious interpretations of motivated human action. To pretend otherwise is either self-delusion or gaslighting. Do you know who absolutely, positively did not kill himself, despite the official narrative that he did? I bet you do.

I’m now too old to be shocked by these kind of machinations, the way Theseus was in The King Must Die. I’ve even started to wonder if Minoan priestess Ariadne was right, in a way. Maybe the realities of an interconnected world of 10 billion people with access to unimaginable wealth and unbelievably destructive weapons, maybe that does have to be managed, in some way. The question might just be, how competent, or benevolent, are those managers? In terms of the theme of these talks, in what ways will the next great fall of man be managed, and if so, to whose benefit? That’s something I’ll be exploring in the future.

Getting back to the question of our own free will, at the individual level, I have a resolution to that, and it’s going to seem unsatisfying, but once I tell you, you’ll have to admit it makes perfect sense. You might even want to adopt it as well. Indeed, as these are both talks and, in some sense, sermons, I’m going to tell you why it’s the morally correct option, and that you must adopt it as well.

I think we need to accept that to the extent that free will exists, it will be impossible to distinguish from randomness, and it can only be exercised to the extent that we accept the possibility that we are pulled by strings that are very hard to see. Thus the correct perspective is to hold a kind of superposition of beliefs. I have free will and I don’t.

Given this superposition, the best framing is to sidestep the uncertainty it creates, and instead focus on your locus of control. That is, free will or not, how rich is the set of scripts you can draw on, and how can you use these to alter your internal and external environment? This framing starts by assuming that you are something akin to an NPC living in a carefully constructed world, then going from there to see what kind of personal agency is possible once you accept these as the initial conditions. Can you cut the strings and grow up to be a real boy? The Pinocchio story is one of accepting responsibility, of moral agency, for your own actions as part of the spiritual growth that lets you graduate from puppet to human. We are born as mimetic, pleasure seeking creatures, but also with the ability to transcend these forces by expanding and exercising our own locus of control.

There are lots of self-help books and videos and podcasts out there which offer practical advice on how to do that. In this series, I’m more concerned with the spiritual implications of what it means to be living at the end of the current human era. As such, my focus in on what we should do with our locus of control, but to answer that we need to first understand the nature of our world and how we perceive it.

That’s a tall order, but we can begin by evaluating some of the theories on the table. Next week I’m going to dive into an idea that starts with the simulation hypothesis and takes it one step further. It’s time to put on our headsets.